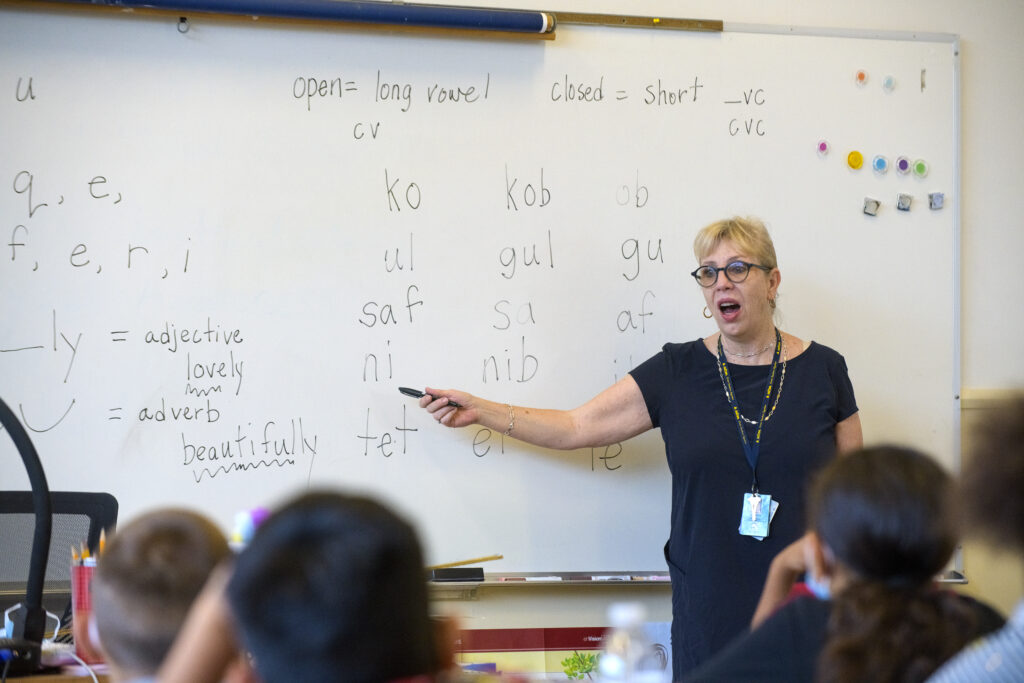

Teacher Jennifer Dare Sparks conducts a reading lesson in her 3rd/4th class at Ethel I. Baker Elementary School in Sacramento, Calif. Thursday, Jun. 2, 2022. Photo credit: Randall Benton / EdSource

Part of nationwide push to bring back phonics, sponsors seek compromise, CTA refuses to negotiate

By DIANA LAMBERT, JOHN FENSTERWALD, ZAIDEE STAVELY, EDSOURCE.org

California’s largest teachers’ union has moved to put the brakes on legislation that mandates instruction, known as the “science of reading,” that spotlights phonics to teach children to read.

The move by the politically powerful California Teachers Association (CTA) puts the fate of Assembly Bill 2222 in question as supporters insist that there is room to negotiate changes that will bring opponents together.

CTA’s complaints include some recently voiced by some advocacy organizations for English learners and bilingual education that oppose the bill and have refused to negotiate any changes to make the bill more acceptable.

The teachers union put its opposition to AB 2222 in writing in a lengthy letter to Assembly Education Committee Chairman Al Muratsuchi last week. The committee is expected to hear the bill, introduced in February, later this month.

The letter includes a checklist of complaints including that the proposed legislation would duplicate and potentially undermine current literacy initiatives, would not meet the needs of English learner students and cuts teachers out of the decision-making process, especially when it comes to curriculum.

“Educators are best equipped to make school and classroom decisions to ensure student success,” the letter said. “Limiting instructional approaches undermines teachers’ professional autonomy and may impede their effectiveness in the classroom.”

Marshall Tuck, CEO of EdVoice, an advocacy nonprofit co-sponsoring the bill, said he was surprised that CTA would oppose legislation that would ensure all teachers are trained to use the latest brain research to teach children how to read.

“Unfortunately, a lot of folks in the field haven’t actually been trained on that, and a lot of the instruction materials in classrooms today don’t align with that,” Tuck said.

Tuck said CTA appears to misunderstand the body of evidence-based research known as the science of reading. It “is not a curriculum and is not a program or a one-size-fits-all approach,” he said. “It will give teachers a foundational understanding of how children learn to read. Teachers will still have a lot of room locally to decide which instructional moves to make on any given day for any given children. So, you’ll still have significant differentiation.”

A nationwide push

California’s push to adopt the science of reading approach to early literacy is in sync with 37 states and some cities, such as New York City, that have passed similar legislation.

States nationwide are rejecting balanced literacy as failing to effectively teach children how to read, since it trains children to use pictures to recognize words on sight, also known as three-cueing. The new method would teach children to decode words by sounding them out, a process known as phonics.

Although phonics, the ability to connect letters to sounds, has drawn the most attention, the science of reading focuses on four other pillars of literacy instruction: phonemic awareness, identifying distinct units of sounds; vocabulary; comprehension; and fluency. It is based on research on how the brain connects letters with sounds when learning to read.

Along with mandating the science of reading approach to instruction, AB 2222 would require that all TK to fifth-grade teachers, literacy coaches and specialists take a 30-hour-minimum course in reading instruction by 2028. School districts and charter schools would purchase textbooks from an approved list endorsed by the State Board of Education.

The legislation goes against the state policy of local control that gives school districts authority to select curriculum and teaching methods as long as they meet state academic standards. Currently, the state encourages, but does not mandate, districts to incorporate instruction in the science of reading in the early grades.

“It’s a big bill,” said Yolie Flores, president of Families in Schools, a co-sponsor. “We’re very proud that it’s a big bill because that means it is truly consequential in the best way possible for children. It’s not a sort of tweak around the edges kind though, it’s the kind of bill that really brings transformation. So we are hoping that the Legislature sees beyond the sort of typical pushback and resistance, and in the end, I think, teachers will see that this was a huge benefit for them.”

Seeking compromise

The bill’s author, Blanca Rubio, D-Baldwin Park, said she took CTA’s seven-page letter not as an outright rejection but as an opportunity for negotiations.

“I’m glad they sent this letter,” she said. “They outline their objections and the reasons why, and that’s something I can work with. It’s not a flat, ‘No, we don’t want you to do it.’ They gave me specific items that I can look at and have a conversation about.”

She said that Assemblymember Muratsuchi asked her to work with the CTA on a compromise. She is also meeting with consultants for Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas, D-Salinas, “to look at the big picture,” she said.

But Flores says the state’s budget problems, with predictions of no money for new programs, may be a bigger hurdle to getting the bill passed than the CTA opposition. The cost of paying for the required professional development for teachers would total $200 million to $300 million, she said. Because it is a mandate, the state would be required to repay districts for the cost.

“That is a drop in the bucket for something so transformational, so consequential,” Flores said. “I hope that the Legislature really comes to that realization. We’re in a budget deficit, but our budget is a statement of priorities.”

Advocates say that it is imperative that California mandate instruction in the science of reading. In 2023, just 43% of California third graders met the academic standards on the state’s standardized test in 2023. Only 27.2% of Black students, 32% of Latino students and 35% of low-income children were reading at grade level, compared with 57.5% of white, 69% of Asian and 66% of non-low-income students.

“It’s foundational,” Flores said. “It’s not the only thing teachers need to know. It’s not the only thing that teachers will need to do and to adhere to, but it’s sort of the basic foundational knowledge of how children’s brains work in order to learn to read.”

The bill would sunset in 2028 when all teachers are required to have completed training. Beginning in July, all teacher preparation programs would be required to teach future educators to base literacy instruction on the science of reading.

Needs of English learners

The CTA and other critics of AB 2222 charge that it ignores the need of English learners for oral language skills, vocabulary and comparison between their home languages and English, which they need in order to learn how to read. Four out of 10 students in California start school as English learners.

Tuck disputes this. “We actually emphasize oral language development,” he said. “This would be the first statute that would say when instructional materials are adopted, and when teachers are trained in the science of reading, they must include a focus on English learners and oral language development.”

Representatives from Californians Together, an advocacy organization for English learners and bilingual education, applauded the CTA’s opposition to the bill. They oppose the bill, rather than suggest amendments, because they disagree with its overall approach.

“We just don’t think this is the right bill to address literacy needs,” said Executive Director Martha Hernandez. “It’s very restrictive. We know that mandates don’t work. It lacks a robust, comprehensive approach for multilingual learners.”

Instead, Californians Together and the California Association for Bilingual Education have both said they would prefer California fund the training of teachers and full implementation of the English Language Arts/English Language Development Framework.

The framework was adopted in 2014 and encourages, but does not mandate, explicit instruction in foundational skills and oral language development for English learners.

The California Language Teachers Association has requested the bill be amended to include information about teaching literacy in languages not based on the English alphabet, such as Japanese, Chinese or Arabic, according to Executive Director Liz Matchett. However, the organization has not yet taken a position on the bill.

“I agree that we want to support all children to be able to read. If they can’t read, they can’t participate in education, which is the one way that is proven to change people’s circumstances,” said Matchett, who teaches Spanish at Gunn High School in Palo Alto. “There’s nothing to oppose about that. I’m still a classroom teacher, and all the time, you get kids in high school who can’t read.”

Education Trust-West urges changes in the bill to center the needs of “multilingual learners” — children who speak languages other than English at home — and to include more oversight and fewer mandates, such as those that may discourage new teachers from entering the profession.

“If our recommended amendments were to be accepted, EdTrust-West would support it as a much-needed solution to California’s acute literacy crisis.”

Claude Goldenberg, professor emeritus of education at Stanford University, said “it was disappointing” to see CTA’s opposition, particularly because the union did not suggest amendments. He said he had met with representatives from CTA and urged them to identify what could be changed in the bill.

In a recent EdSource commentary, Goldenberg urged opponents to “do the right thing for all students. AB 2222’s introduction is an important step forward on the road to universal literacy in California. We must get it on the right track and take it across the finish line.”

Referring to the CTA’s opposition, Goldenberg said, “Obviously my urgings fell flat. They identified why they’re opposing, but there’s no indication of any possible re-evaluation.”

Goldenberg, who served on the National Literacy Panel, which synthesized research on literacy development among children who speak languages other than English, has called on the bill’s authors to amend it to include a more comprehensive definition of the “science of reading” and include more information about teaching students to read in English as a second language and in their home languages.

The CTA has changed its position on bills related to literacy instruction in the last two years. It had originally supported Senate Bill 488, which passed in 2022. The legislation requires a literacy performance assessment for teachers and oversight of literacy instruction in teacher preparation. The union is now in support of a bill that would do away with both.

The change of course was attributed to a survey of 1,300 CTA members, who said the assessment caused stress, took away time that could have been used to collaborate with mentors and for teaching, and did not prepare them to meet the needs of students, according to Leslie Littman, vice president of the union, in a prior interview.

Veteran political observer Dan Schnur said he’s not surprised CTA would oppose the bill since some of its political allies are against it; the question is how important CTA considers the bill.

“If it becomes a pitched battle, CTA will have to decide whether it is one of its highest priorities in this session,” he said.

Gov. Gavin Newsom hasn’t indicated his position yet, but Schnur, the press secretary for former Gov. Pete Wilson, who teaches political communications at UC Berkeley and USC, said, “This is not the type of fight Newsom needs or wants right now. If he has strong feelings, it’s hard to see him going to war for or against.”

Leave a Reply